Urdu in Paint - Bruce Colburn

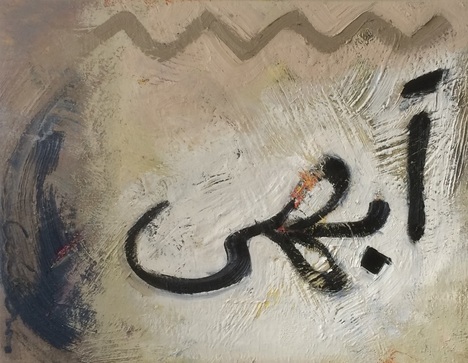

Abhi (Now), detail, oil on linen, 2016

|

Why a show of Urdu in Painting?

This show is a celebration of Urdu, a language I started learning 10 years ago to the day. We were moving to Pakistan and I wanted to be able to read the national language. At the time I had no idea that Urdu would become so important in my life, and by extension, my painting. |

L’Ourdou, qui appartient au groupe des langues indo européennes, est la langue nationale du Pakistan et des musulmans de l’Inde.

Pourquoi cette expo ? Cette expo se veut une célébration de la langue Ourdou, que j’ai commencé à apprendre il y a 10 ans. Nous étions alors en partance pour le Pakistan et je voulais être en mesure de lire la langue locale. A ce moment-là, je ne présageais pas l’importance que cette langue allait prendre dans ma vie, et par extension, dans ma peinture. |

The Long March I (detail), collection of Supriya Madhavan and Zahid Hasnain, watercolor, 2008

|

Graphic and lovely, Urdu is particularly suited to art. It’s a combination of Persian and Arabic (and a smattering of other stuff) written in a cascading calligraphic script called Nastaʿlīq. Urdu is easily the most beautiful written language in the world, in my opinion.

|

Graphique et envoûtant, l’Ourdou se marie particulièrement bien avec la peinture. Il utilise le Nastaʿlīq, une écriture en cascade qui participe de l’arabe et du persan. Je la trouve particulièrement belle.

|

The Long March II, watercolor, 2008

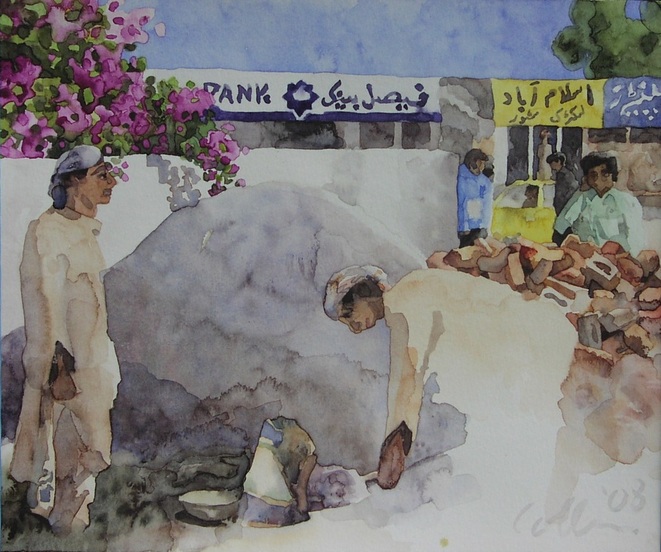

Mosque in Islamabad, watercolor, 2008

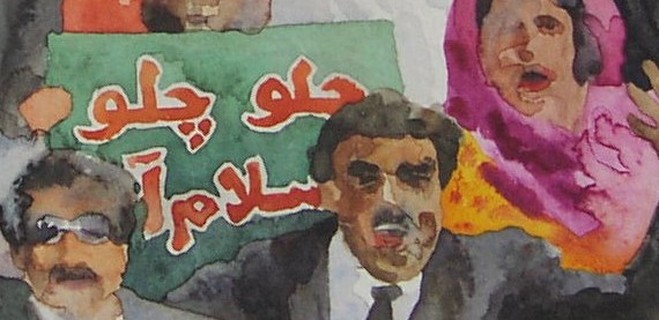

Dancing Lawyers, watercolor, 2008

|

Urdu first started cropping up in my watercolors. I was spending a lot of time in the streets, markets, and mosques, painting everyday scenes. Artistic fidelity required inclusion of the shop signs, graffiti, and banners in Urdu.

|

L’Ourdou a commencé par s’inviter dans les aquarelles que je réalisais dans les rues, les marchés, et les mosquées. La fidélité artistique me demandait d’inclure les enseignes, les panneaux, et les banderoles qui faisaient partie de ces scènes de la vie ordinaire.

|

Atta Crisis (Demonstration over sky-rocketing wheat flour prices), watercolor, 2008

Two Day Laborers, watercolor, 2007

|

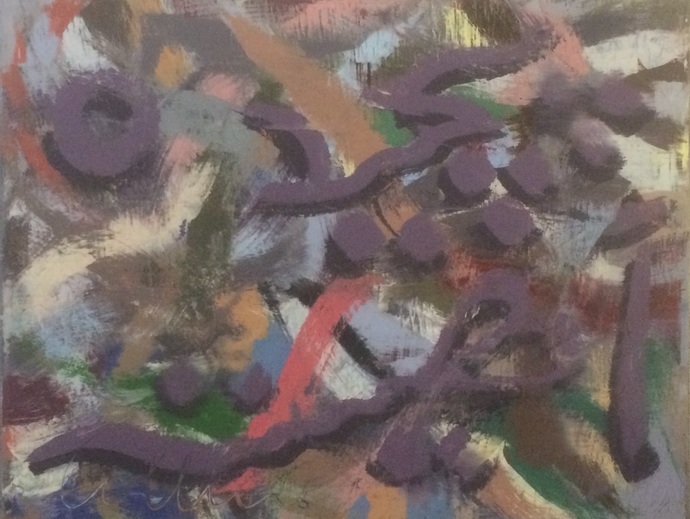

So lovely and expressive did I find the script that I began wondering if it also had a place in my abstract oils. After all, the style of those oils was fluid and calligraphic. My first experiment was Ap Ka Nam Kya Hai? The tentative forays led, over time, to more in-depth studies, series of works in which Urdu had become the paintings’ very subject.

|

Mais ces mots, si beaux et si expressifs, m’interpellaient. Est-ce qu’ils auraient aussi leur place dans les huiles abstraites que je peignais parallèlement ? Ma première tentative dans ce sens fut Ap Ka Nam Kya Hai. Au fil du temps naissaient d’autres essais, puis des séries dans lesquelles les mots en Ourdou sont devenus le sujet du

tableau (comme pour Abhi). |

Ap Ka Nam Kya Hai? (What's your name?), 53 x 42 inches, oil on linen, 2009

Naqashi (study), 40 x 31 inches, oil on line, 2015

Naqashi, 33 x 42 inches, oil on linen, 2016

|

Urdu is now so central to my work that I deem it worth a show, a spotlight on this piece of my overall artistic puzzle.

|

L’écriture de l’Ourdou est devenue tellement centrale dans ma procédure artistique que j’estime qu’elle mérite une expo à part, regroupant une bonne partie de ces oeuvres.

|

|

Why an on-line show?

After 34 brick-and-mortar shows, I decided to give virtual a try. There are practical reasons, of course: we just moved and I don’t know any bricks and mortars here now. But the main reason lies elsewhere. My goal in painting is to make unmannered work (having no style at all) - the only door that opens into the realm of art. "Unmannered" means never repeating yourself, always taking risks, shunning expediency for necessity. The motto of the unmannered is: Why not? I've never had an on-line show, so, Why not? |

Pourquoi une expo en ligne ?

Après 34 expositions traditionnelles dans des galeries, j’ai enfin décidé de faire un essai dans le virtuel. Il y avait, bien sûr, des raisons pratiques à cette décision : nous venons de déménager et je n’ai pas le temps de chercher un lieu d’expo. Mais la véritable raison tient à l’importance que j’attache à l’expérience dans mon oeuvre. En effet, la quête artistique supporte mal la répétition et ne tolère surtout pas d’hésitation devant une nouveauté, quelle qu’elle soit. Donc, pourquoi ne pas essayer l’exposition virtuelle, pour une fois ? |

Urdu Script study I, 15 x 20 inches, oil on linen, 2009

Urdu Script study II, 15 x 20 inches, oil on linen, 2009

Turning 50 (detail), oil on linen, 2014

Turning 50, 62 x 50 inches, oil on linen, 2014

Abhi (Now) study, 15 x 20 inches, oil on linen, 2016

Abhi (Now), 53 x 42 inches, oil on linen, 2016

Urdu Script study III, 15 x 20 inches, oil on linen, 2010

SHOW NOTES

I spent much of the spring with a book about a 28-line poem in French and various ways of translating it into English*. The core of the book is the hundreds of English versions, but like so many great books, it’s loaded with diversions, meandering through all kinds of kooky:

This reading was great accompaniment to the process of putting together this show. I was, after all, working through questions of translation, language, symbols, and meaning, so following someone else’s similar wanderings was entertaining and instructive. I gradually came to understand why I find Urdu so appealing.

Urdu words offer three things that I now see are indispensable to painting. First, sheer esthetic beauty – the script is lovely. Second, useful symbols. Words are symbols – pictures standing for things and ideas. And Urdu words, because of their foreigness to me, are very useful because they have the distance and over-arching reach that English and French words, steeped as they are in the specific and familiar, just don’t provide. So, for instance, the Urdu word for “Now,” can be used to address the philosophical opposition between the present and other time (past/future) whereas “Now” in English seems to me just a marker in time for sequencing tasks. Third, Urdu’s right-to-left script is a constant warning of the human tendency to confuse habit with truth. It’s a reminder that even though French and English read left-to-right, you can’t just say, “Reading is something that happens left-to-right." These three qualities make a very foreign language like Urdu an ideal subject for my painting, for painting must, in my view, have all three: esthetic appeal, philosophical distance (or perspective, if you prefer), and the ability to challenge any assumption that is based on previous experience.

This is why Urdu made the leap from background detail in the watercolors to becoming the paint’s very subject and raison d’être in the abstract oils.

This is as much background info as I feel comfortable giving as “show notes:” I’m always wary of bending the viewer’s ear (or worse, breaking it). But if you have questions about the paintings, their titles, the process of their making, or anything really, just drop me a line and I promise to answer it as best I can.

* Le Ton beau de Marot, In Praise of the Music of Language by Douglas Hofstadter (thanks, Ruth!)

I spent much of the spring with a book about a 28-line poem in French and various ways of translating it into English*. The core of the book is the hundreds of English versions, but like so many great books, it’s loaded with diversions, meandering through all kinds of kooky:

This reading was great accompaniment to the process of putting together this show. I was, after all, working through questions of translation, language, symbols, and meaning, so following someone else’s similar wanderings was entertaining and instructive. I gradually came to understand why I find Urdu so appealing.

Urdu words offer three things that I now see are indispensable to painting. First, sheer esthetic beauty – the script is lovely. Second, useful symbols. Words are symbols – pictures standing for things and ideas. And Urdu words, because of their foreigness to me, are very useful because they have the distance and over-arching reach that English and French words, steeped as they are in the specific and familiar, just don’t provide. So, for instance, the Urdu word for “Now,” can be used to address the philosophical opposition between the present and other time (past/future) whereas “Now” in English seems to me just a marker in time for sequencing tasks. Third, Urdu’s right-to-left script is a constant warning of the human tendency to confuse habit with truth. It’s a reminder that even though French and English read left-to-right, you can’t just say, “Reading is something that happens left-to-right." These three qualities make a very foreign language like Urdu an ideal subject for my painting, for painting must, in my view, have all three: esthetic appeal, philosophical distance (or perspective, if you prefer), and the ability to challenge any assumption that is based on previous experience.

This is why Urdu made the leap from background detail in the watercolors to becoming the paint’s very subject and raison d’être in the abstract oils.

This is as much background info as I feel comfortable giving as “show notes:” I’m always wary of bending the viewer’s ear (or worse, breaking it). But if you have questions about the paintings, their titles, the process of their making, or anything really, just drop me a line and I promise to answer it as best I can.

* Le Ton beau de Marot, In Praise of the Music of Language by Douglas Hofstadter (thanks, Ruth!)